library(tidyverse)

library(haven) # for importing SPSS data

library(posterior) # for summarizing posterior draws

library(bayesplot) # for convergence plots

theme_set(theme_classic() +

theme(panel.grid.major.y = element_line(color = "grey92")))

In the previous note, we learn about the Metropolis algorithm. While the algorithm is very general and easy to implement, it is inefficient because the effective sample size is only about 1/4 of the actual number of draws for a one-parameter model. The Meteropolis algorithm usually gets stuck when there are multiple parameters. Therefore, until about 2010, many Bayesian analyses relied on a more efficient algorithm—the Gibbs sampler. The Gibbs sampler uses conjugate priors on the conditional posterior distributions to get proposal values with high acceptance probability (it’s 100%). We’ll also see the normal model with two parameters: mean and variance.

Data

The data set was from one of the studies reported in a paper published in Psychological Science in 2014. The authors compared participants’ performance on conceptual questions after taking notes either using laptops or notebooks (“longhand”). Let’s import the data directly from the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/qrs5y/):

# Use haven::read_sav() to import SPSS data

nt_dat <- read_sav("https://osf.io/qrs5y/download")

One outcome variable the authors studied is the number of words in

participants’ notes. Here are the distributions of the variable

wordcount for the two conditions (0 = laptop, 1 =

longhand).

ggplot(nt_dat, aes(x = wordcount)) +

geom_histogram(bins = 10) +

facet_wrap(~ condition)

The variable is somewhat skewed. We’ll focus on the control group

(laptop) first, so let’s create a variable for that data.

We’ll also divide the count by 100.

(wc_laptop <- nt_dat$wordcount[nt_dat$condition == 0] / 100)

#> [1] 4.20 4.61 5.72 4.47 3.34 1.27 2.65 3.40 2.43 2.55 2.73 2.26 3.16

#> [14] 2.47 3.25 1.67 4.49 4.77 1.67 5.19 3.00 2.98 1.59 2.23 4.39 2.29

#> [27] 1.52 2.13 3.11 3.82 2.62The Normal Model

While only an approximation, the normal distribution is a popular

choice for modeling variables that are relatively symmetric and have

more than a few discrete values. The normal distribution has two

parameters; in some situations, there are advantages to choosing a

certain parameterization. With the Gibbs sampler, we will parameterize

it using the mean parameter, μ,

and the variance parameter, σ2. The model is wc_laptopi∼N(μ,σ2)

Conjugate (Actually “Semiconjugate”) Priors

It can be shown that when σ2 is known, a conjugate prior to μ is a normal prior, meaning that the posterior is also normal. However, when σ2 is unknown, the prior distribution needs to be a joint distribution of two parameters.

What we can do is to consider the conditional distribution of a parameter. So instead of drawing a posterior sample from the joint posterior, P(μ,σ2∣y), we consider each parameter separately, by drawing from the conditional of P(σ2∣μ(s−1),y) first, and then from P(μ∣σ2=σ2(s),y) with σ2(s) being the previous draw, and then continuing with P(σ2∣μ(s),y). The advantage to do so is because we can use a conjugate normal prior for μ when conditioning on σ2. We also have a conjugate prior for σ2 when conditioning on μ, which will be discussed later. Here is how the algorithm works:

- Set an initial value for σ2(1)

- At iteration s, given sample σ2(s−1), sample μ(s) from the conditional posterior, P(μ∣σ2(s),y)

- Given μ(s), sample σ2(s) from the conditional posterior, P(σ2∣μ(s−1),y)

- Repeat steps 2 and 3

It can be shown that with this Gibbs algorithm, the posterior draws will be from the joint posterior of P(μ,σ2∣y).

Below I provide more details of the conjugacy. The actual detail is not the most important for this class because, in practice, the computation will likely be handled by the software. You may want to, however, pay attention to the suggested meanings of the hyperparameters:

- μ0: Prior mean

- τ20: Prior variance (i.e., uncertainty) of the mean

- ν0: Prior sample size for the variance

- σ20: Prior expectation of the variance

For μ∣σ2

A conjugate prior for μ∣σ2 is μ∼N(μ0,τ20), which gives the posterior conditional μ∣σ2,y∼N(μn,τ2n),

For σ2∣μ

A conjugate prior for μ∣σ2 is from the Inverse-Gamma family: σ2∼Inv-Gamma(ν0/2,ν0σ20/2). You usually only hear about the Inverse-Gamma distribution in Gibbs sampling, mainly because of conjugacy. As the name suggested, the Inverse-Gamma distribution is the distribution of the inverse of a variable that follows a Gamma distribution. So we also write 1/σ2∼Gamma(ν0/2,ν0σ20/2).

The posterior is also Inverse-Gamma, with 1/σ2∣μ2,y∼Gamma(νn/2,νnσ2n[μ]/2),

Prior, Model, and Posterior

We will use some weakly informative priors, written in the following equations:

Model: wc_laptopi∼N(μ,σ2)

The priors are very weak. We also assume that the priors are independent, which is commonly the case. Here are some simulated data from these priors:

set.seed(2259)

num_draws <- 100

mu <- rnorm(num_draws, mean = 5, sd = 10)

inv_sigma2 <- rgamma(num_draws,

shape = 1 / 2, rate = 1 / 2)

num_obs <- length(wc_laptop)

# Initialize an S by N matrix to store the simulated data

y_tilde <- matrix(NA,

nrow = num_draws,

ncol = num_obs)

for (s in seq_len(num_draws)) {

mu_s <- mu[s]

sigma2_s <- 1 / inv_sigma2[s]

y_tilde[s, ] <- rnorm(num_obs, mean = mu_s, sd = sqrt(sigma2_s))

}

# Plot the simulated data (in lighter lines)

# and the current data (in the darker line)

ppc_dens_overlay(wc_laptop, yrep = y_tilde)

The plot shows the types of data one can get. One can do better by avoiding the negative values if desired.

Gibbs Sampler

The following is the full Gibbs sampler for the above normal model.

# Sufficient statistics from data

ybar <- mean(wc_laptop) # sample mean

s2y <- var(wc_laptop) # sample variance

n <- length(wc_laptop) # sample size

# Hyperparameters

mu_0 <- 5

sigma2_0 <- 1

tau2_0 <- 10^2

nu_0 <- 1

# Initialize the Gibbs sampler

set.seed(2120)

num_draws <- 10000

num_warmup <- num_draws / 2

num_chains <- 2

# Initialize a 3-D array (S x # chains x 2 parameters)

post_all_draws <- array(

dim = c(num_draws, num_chains, 2),

dimnames = list(NULL, NULL, c("mu", "sigma2"))

)

# Step 1: starting values for sigma2

post_all_draws[1, 1, "sigma2"] <- 1 # for chain 1

post_all_draws[1, 2, "sigma2"] <- 3 # for chain 2

for (s in seq_len(num_draws - 1)) {

for (j in seq_len(num_chains)) {

sigma2_s <- post_all_draws[s, j, "sigma2"]

# Step 2: Sample mu from the conditional posterior

tau2_n <- 1 / (1 / tau2_0 + n / sigma2_s)

mu_n <- tau2_n * (mu_0 / tau2_0 + n * ybar / sigma2_s)

mu_new <- rnorm(1, mean = mu_n, sd = sqrt(tau2_n))

post_all_draws[s + 1, j, "mu"] <- mu_new

# Step 3: Sample sigma2 from the conditional posterior

nu_n <- nu_0 + n # you could put this line outside the loop

sigma2_n <- 1 / nu_n *

(nu_0 * sigma2_0 + (n - 1) * s2y + (ybar - mu_new)^2)

sigma2_new <- 1 / rgamma(1,

shape = nu_n / 2,

rate = nu_n * sigma2_n / 2

)

post_all_draws[s + 1, j, "sigma2"] <- sigma2_new

}

}

# Draws after warm-up

post_draws <- post_all_draws[- (1:num_warmup), , ]

Visualizing the Jumps

The plot below shows the jumps for 20 iterations in one chain, with the intermediate steps

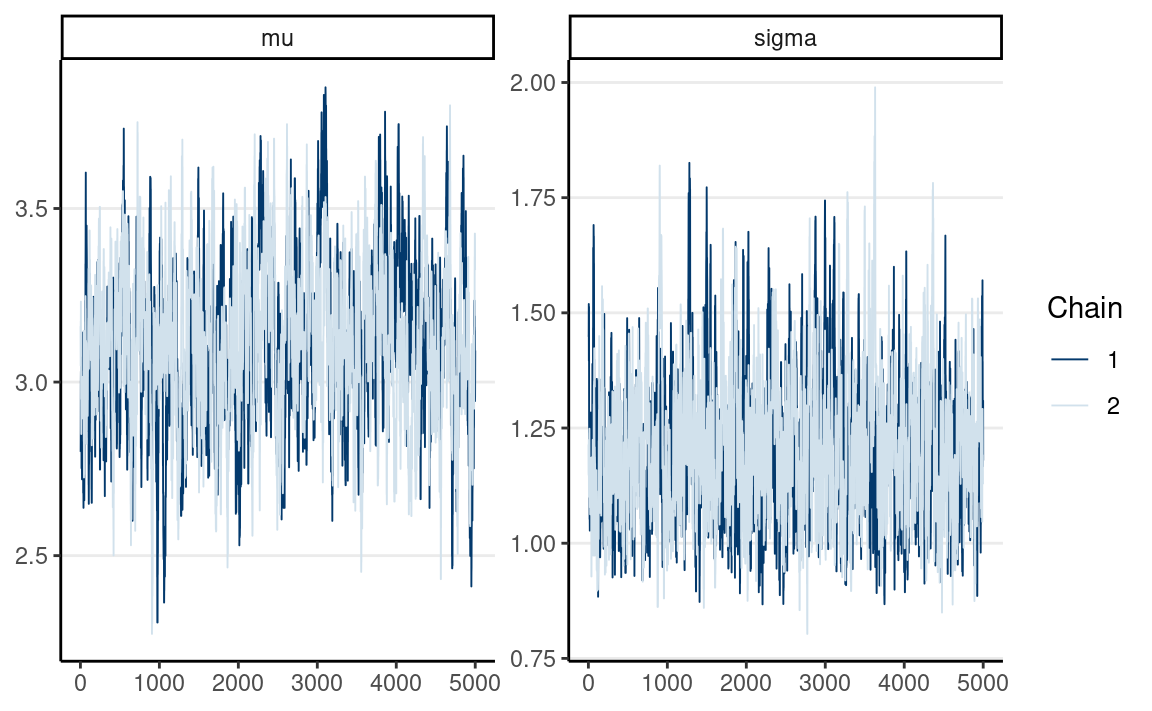

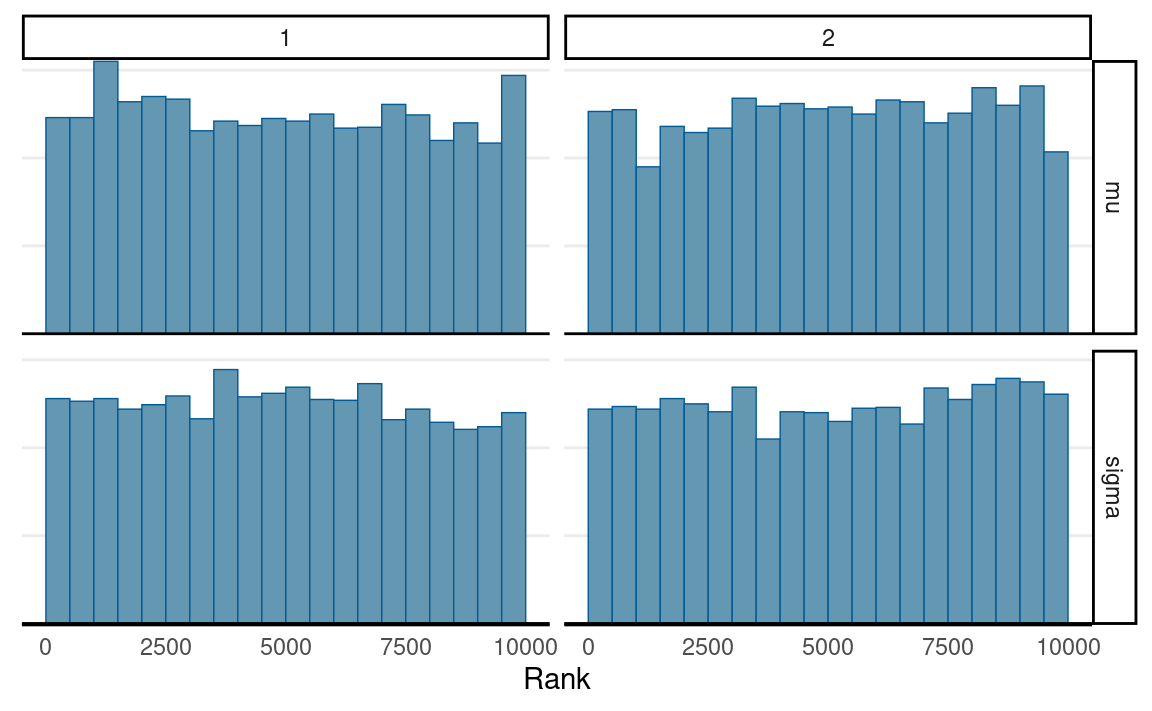

Convergence Check

# Convert to `draws_array` object to use the following functions

post_draws_array <- as_draws_array(post_draws)

# Trace plots

mcmc_trace(post_draws_array) # good mixing

# Rank histograms

mcmc_rank_hist(post_draws_array) # good mixing

# Summary (with rhat and ESS)

summarize_draws(post_draws_array)

#> # A tibble: 2 × 10

#> variable mean median sd mad q5 q95 rhat ess_bulk

#> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 mu 3.10 3.10 0.213 0.211 2.75 3.45 1.00 9928.

#> 2 sigma2 1.40 1.33 0.378 0.337 0.904 2.11 1.00 10189.

#> # … with 1 more variable: ess_tail <dbl>

As can be seen, the ESS is very high, indeed much higher than that obtained with the Metropolis algorithm.

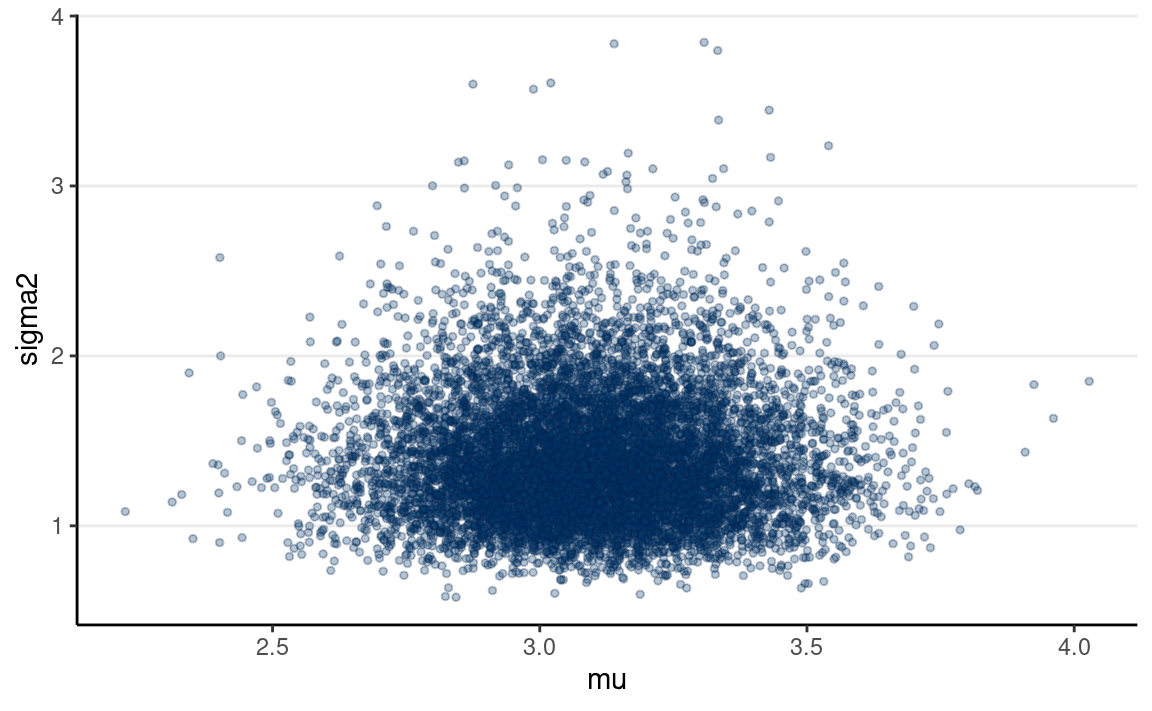

Visualizing the Marginal and Joint Posterior

mcmc_areas(post_draws_array) # marginal

mcmc_scatter(post_draws_array, # joint

size = 1, alpha = 0.3) # make points smaller

Posterior Predictive Check

We can check whether the simulated data based on the posterior look like the observed data.

num_draws <- 100

num_obs <- length(wc_laptop)

# Initialize an S by N matrix to store the simulated data

y_tilde <- matrix(NA,

nrow = num_draws,

ncol = num_obs)

for (s in seq_len(num_draws)) {

mu_s <- post_draws[s, 1, "mu"]

sigma2_s <- post_draws[s, 1, "sigma2"]

y_tilde[s, ] <- rnorm(num_obs, mean = mu_s, sd = sqrt(sigma2_s))

}

# Plot the simulated data (in lighter lines)

# and the current data (in the darker line)

ppc_dens_overlay(wc_laptop, yrep = y_tilde)

The simulated data are not too far off from the observed data. Just that the simulated data also can get negative values.

Limitation of Gibbs Sampler

The Gibbs sampler has been popular due to its computational efficiency for many problems. However, there are situations that it works less well, such as when some parameters are highly correlated in the posterior, in which case a Gibbs sampler may get stuck. Another limitation is that Gibbs samplers require the use of conjugate priors. On the one hand, sometimes researcher beliefs may be better expressed in distributions other than the conjugate family. On the other hand, some conjugate families, such as the inverse Gamma distribution, are hard to work with and may yield suboptimal results in small sample situations.

The Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm

The Metropolis-Hastings (MH) algorithm is a generalization of the Metropolis algorithm, where it allows for more than one parameter and can use a proposal distribution that is not symmetric. It is not as efficient as the Gibbs sampler but can accommodate non-conjugate prior distributions. Note that the proposal distribution needs to have the same dimension as the posterior so that the proposal is a vector in the parameter space. For example, we need a bivariate proposal density with μ and σ.

Below is an example using a bivariate normal distribution for the

proposal. While we can choose how correlated the variables are in the

proposal, for simplicity, I just consider zero correlation and equal

SD for both dimensions. I also parameterize the normal

distribution by the mean, μ, and

the standard deviation (instead of the variance), σ. The priors are: μ∼N(5,102)σ∼N+(0,3),

Here is the code for the MH algorithm:

# Define a function to compute values proportional to p(y | th) * p(th)

prior_times_lik <- function(mu_sigma, y = wc_laptop) {

mu <- mu_sigma[1]

sigma <- mu_sigma[2]

# Return 0 if sigma is out of range

if (sigma < 0) return(0)

# Joint prior = product of marginal priors

pth <- dnorm(mu, mean = 5, sd = 10) *

# half-normal is proportional to normal in [0, infinity)

dnorm(sigma, sd = 3)

# Likelihood

py_given_th <- prod(dnorm(y, mean = mu, sd = sigma))

pth * py_given_th

}

# Define a function for generating data from the proposal distribution

generate_proposal <- function(mu_sigma, sd = 0.1) {

rnorm(length(mu_sigma), mean = mu_sigma, sd = sd)

}

# Initialize the Metropolis algorithm

set.seed(1051) # set the seed for reproducibility

num_draws <- 10000

num_warmup <- num_draws / 2

num_chains <- 2

# Initialize a 3-D array (S x # chains x 2 parameters)

post_all_draws <- array(

dim = c(num_draws, num_chains, 2),

dimnames = list(NULL, NULL, c("mu", "sigma"))

)

# Step 1: starting value

post_all_draws[1, 1, ] <- c(1, 1) # for chain 1

post_all_draws[1, 2, ] <- c(8, 3) # for chain 2

# counter for tracking acceptance rate

num_accepted <- rep(0, num_chains)

for (s in seq_len(num_draws - 1)) {

for (j in seq_len(num_chains)) {

current_par <- post_all_draws[s, j, ]

# Generate proposal vector

proposed_par <- generate_proposal(current_par, sd = 0.1)

# Compute acceptance probability

prob_accept <- min(

1,

prior_times_lik(proposed_par) /

prior_times_lik(current_par)

)

# Determine whether to make the jump

if (runif(1) < prob_accept) {

post_all_draws[s + 1, j, ] <- proposed_par

if (s + 1 >= num_warmup) {

num_accepted[j] <- num_accepted[j] + 1

}

} else {

post_all_draws[s + 1, j, ] <- current_par

}

}

}

# Draws after warm-up

post_draws <- post_all_draws[- (1:num_warmup), , ]

# Acceptance rate

sum(num_accepted) / length(post_draws)

#> [1] 0.3638Convergence

# Convert to `draws_array` object to use the following functions

post_draws_array <- as_draws_array(post_draws)

# Trace plots

mcmc_trace(post_draws_array) # good mixing

# Rank histograms

mcmc_rank_hist(post_draws_array) # good mixing

# Summary (with rhat and ESS)

summarize_draws(post_draws_array)

#> # A tibble: 2 × 10

#> variable mean median sd mad q5 q95 rhat ess_bulk

#> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 mu 3.11 3.11 0.230 0.227 2.72 3.49 1.01 305.

#> 2 sigma 1.20 1.19 0.152 0.145 0.985 1.48 1.00 694.

#> # … with 1 more variable: ess_tail <dbl>

As can be seen, ESS is much lower, so more iterations will be needed with MH.