library(psych, include.only = "pairs.panels") # only load one function

library(tidyverse)

library(bayesplot)

theme_set(theme_classic() +

theme(panel.grid.major.y = element_line(color = "grey92")))

Steps of Bayesian Data Analysis

Some authors described the process as “turning the Bayesian Crank,” as the same workflow applies to a variety of research scenarios.

Adapted from Kruschke (2015, p.25), I conceptualize Bayesian data analysis as the following steps:

- Identify/Collect the data required to answer the

research questions.

- As a general recommendation, it is helpful to visualize the data to get a sense of how the data look, as well as to inspect for any potential anomalies in the data collection.

- Choose a statistical model for the data in relation to the research questions. The model should have sound theoretical justification and have parameters that are meaningful for the research questions.

- Specify prior distributions for the model parameters. Although this is a subjective endeavor, the priors chosen should be at least sensible to a skeptical audience.

- Obtain the posterior distributions for the model

parameters. As described below and later in the course, this can be

obtained by analytical or various mathematical approximations.

- For mathematical approximations, one should check the algorithms for convergence to make sure the results closely mimic the target posterior distributions.

- Conduct a posterior predictive check to examine the

fit between the model and the data, i.e., whether the chosen model with

the estimated parameters generate predictions that deviate from the data

being analyzed on important features.

- If the model does not fit the data, one should go back to step 2 to specify a different model.

- If the fit between the model and the data is deemed satisfactory, one can proceed to interpret the results in the context of the research questions. It is also important to visualize the results in ways that are meaningful for the analysis.

Beta-Bernoulli Example

We will be using a built-in data set in R about patients diagnosed with AIDS in Australia before July 1, 1991. Here is a description of the variables (from the R documentation):

state: Grouped state of origin: “NSW”includes ACT and “other” is WA, SA, NT, and TAS.sex: Sex of patient.diag:(Julian) date of diagnosis.death: (Julian) date of death or end of observation.status: “A” (alive) or “D” (dead) at end of observation.T.categ: Reported transmission category.age: Age (years) at diagnosis.

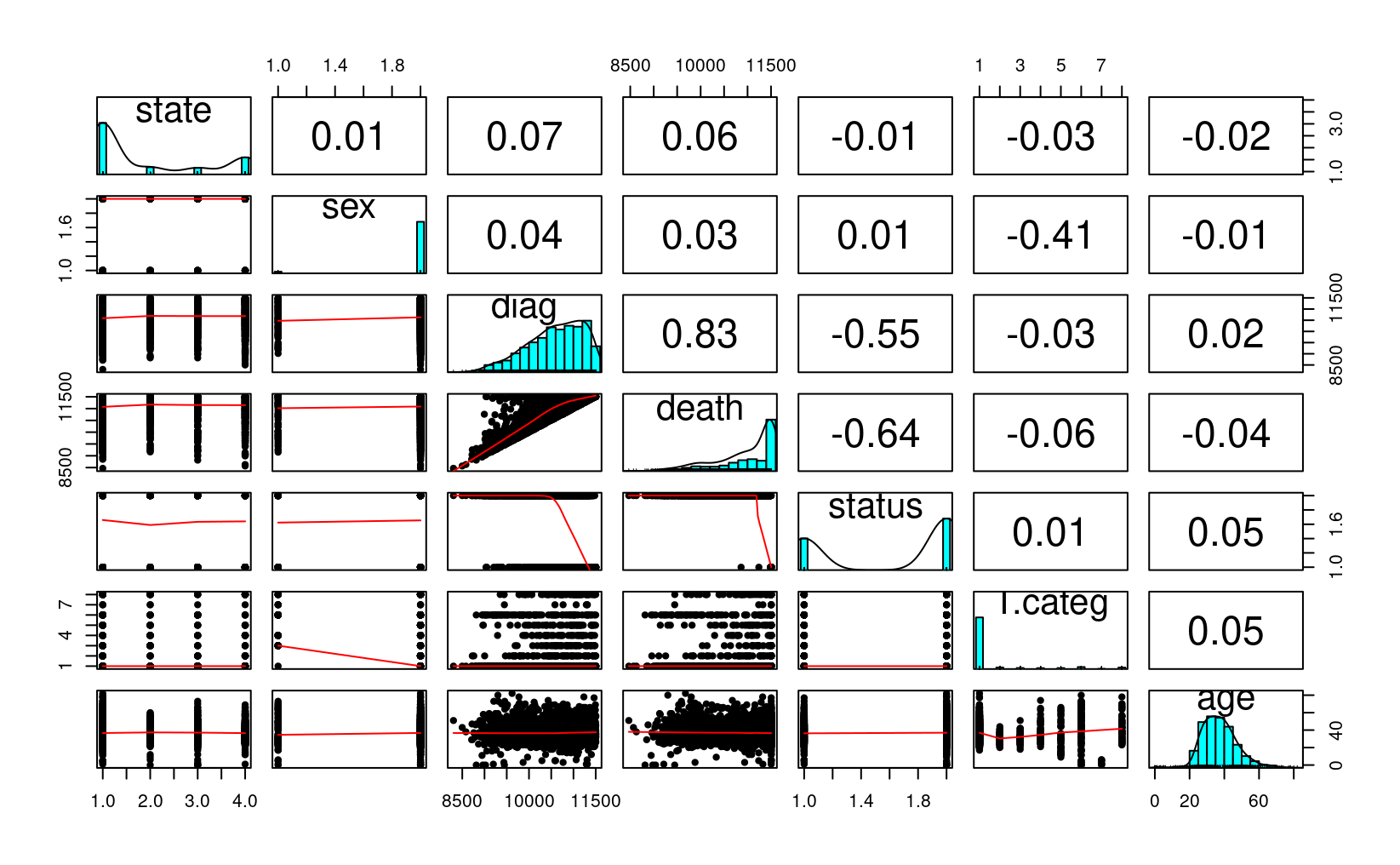

You should always first plot your data and get some summary statistics:

#> state sex diag death status T.categ age

#> 1 NSW M 10905 11081 D hs 35

#> 2 NSW M 11029 11096 D hs 53

#> 3 NSW M 9551 9983 D hs 42

#> 4 NSW M 9577 9654 D haem 44

#> 5 NSW M 10015 10290 D hs 39

#> 6 NSW M 9971 10344 D hs 36pairs.panels(Aids2, ellipses = FALSE)

We will be using the status variable. Our simple

research question is:

What was the death rate of AIDS in Australia when the data were collected?Bernoulli Model

If we assume that the outcome of the observations are exchangeable,

meaning that the observations can be reordered in any way and still

gives the same inference, then one can choose a model: yi∼Bern(θ)for i=1,2,…,N

- yi = status of observation i (0 = “A”, 1 = “D”)

- N = number of patients in the data set

- θ = probability of “D”

The model states that: the sample data y follows a Bernoulli distribution with n with a parameter θ

Exchangeability

To illustrate exchangeability in an example, say we take 6 rows in our data set:

| state | sex | diag | death | status | T.categ | age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NSW | M | 10905 | 11081 | D | hs | 35 |

| 31 | NSW | F | 10961 | 11504 | A | id | 30 |

| 1802 | QLD | F | 9495 | 9753 | D | blood | 66 |

| 1811 | QLD | M | 10770 | 11504 | A | hsid | 29 |

| 2129 | VIC | M | 8499 | 8568 | D | hs | 43 |

| 2137 | VIC | M | 9055 | 9394 | D | hs | 29 |

Now, when we reorder the column status to something

like:

| state | sex | diag | death | status | T.categ | age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NSW | M | 10905 | 11081 | D | hs | 35 |

| 31 | NSW | F | 10961 | 11504 | A | id | 30 |

| 1802 | QLD | F | 9495 | 9753 | D | blood | 66 |

| 1811 | QLD | M | 10770 | 11504 | D | hsid | 29 |

| 2129 | VIC | M | 8499 | 8568 | A | hs | 43 |

| 2137 | VIC | M | 9055 | 9394 | D | hs | 29 |

If the results are expected to be the same, then we say that the observations are assumed exchangeable. It happens when we assume that all observations have one common mean. However, if we think that there is a mean for females and a different mean for males, we cannot reorder the outcome randomly because they are no longer exchangeable (i.e., you cannot exchange a female score for a male score and expect to get the same results).

Exchangeability: A set of observations is said to be exchangeable if their joint probability distribution stays the same under all permutations. Roughly speaking, it means that the observations can be reordered and still provide the same inferences.

Check the Support

The first thing is to identify the support of the parameter, θ. Because θ is a probability, its support is [0,1], meaning that it is continuous and can take any value from 0 to 1. For a continuous parameter, there are infinitely many possible values, and it is impossible to specify our beliefs for each value. So more commonly, we choose a probability density function with the same support as the parameter to express our prior belief.

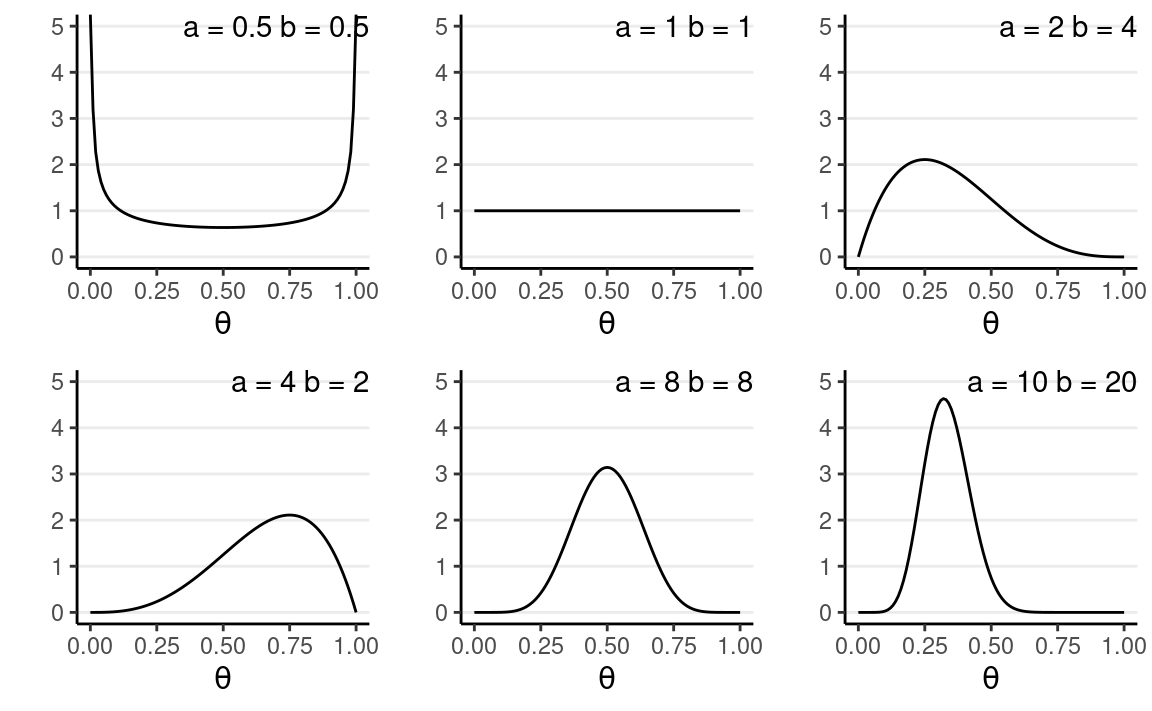

Conjugate Prior: Beta Distribution

A commonly used family of prior distributions for a

Bernoulli/binomial model is the Beta distribution, which has

two parameters. We can write the prior as P(θ)∼Beta(a,b)

a and b are the two parameters. Here are a few examples:

You will notice that when a>b, there will be more density closer to the right region (i.e.,

larger θ), and vice versa.

Also, when a and b become larger, the variance

decreases.

A nice interpretation of a and b in a Beta prior distribution is to consider

- a−1 = number of prior ‘successes’ (e.g., “D”)

- b−1 = number of prior ‘failures’ (e.g., “A”)

Therefore, with Beta(1,1), one has seen 0 prior success and 0 failure, meaning that there is no prior information (i.e., noninformative). Therefore, it makes sense that all θ values are equally likely. On the other hand, if one chooses Beta(10,20), one has seen 9 prior successes and 19 prior failures, so one has quite a lot of prior information (indeed more than the data with only 10 observations), so this is a strong prior.

The smaller the variance of the prior distribution, the stronger one’s belief before looking at the data, the more prior information

So by manipulating the values of a and b, which are sometimes called hyperparameters, you can control the shape of the prior distribution as well as its strength, so it is quite flexible. Another advantage of using a beta prior is that it is a conjugate prior of the Bernoulli model, which means that the posterior distribution P(θ∣y) is also a beta distribution, the same as the prior distribution, although with different parameter values.

Conjugate Prior: For a specific model, conjugate priors yield posterior distributions in the same distribution family as the priors

Conjugacy greatly simplifies the computational burden for Bayesian analyses, so conjugate priors are almost the only ones used in earlier literature. However, this limited the applications of Bayesian methods, as for many problems, no conjugate priors can provide a realistic representation of one’s belief. Modern Bayesian analysis instead relies on simulation-based methods to approximate the posterior distribution, which can accommodate almost any kind of prior distribution. Aside from a few examples in this note, mainly for pedagogical purposes, we will be using simulation-based methods in the coming weeks.

Proof of Conjugacy*

To derive the form of the posterior, first recognize that the Beta distribution has the form:

P(θ)=B−1(a,b)θa−1(1−θ)b−1∝θa−1(1−θ)b−1

Where B(⋅) is the beta function which is not very important for the class. As the density function is a function of θ, it suffices to write only the terms that involve θ.

Similarly, P(y∣θ)∝θz(1−θ)N−z.

Therefore,

P(θ∣y)∝P(y∣θ)P(θ)∝θz(1−θ)N−zθa−1(1−θ)b−1=θa+z−1(1−θ)b+N−z−1.

If we let a∗=a+z, b∗=b+N−z, we can see that P(θ∣y) is in the same form as the prior with a and b replaced by a∗ and b∗. Therefore, the posterior is also a beta distribution. So the beta distribution is a conjugate prior for the Bernoulli model.

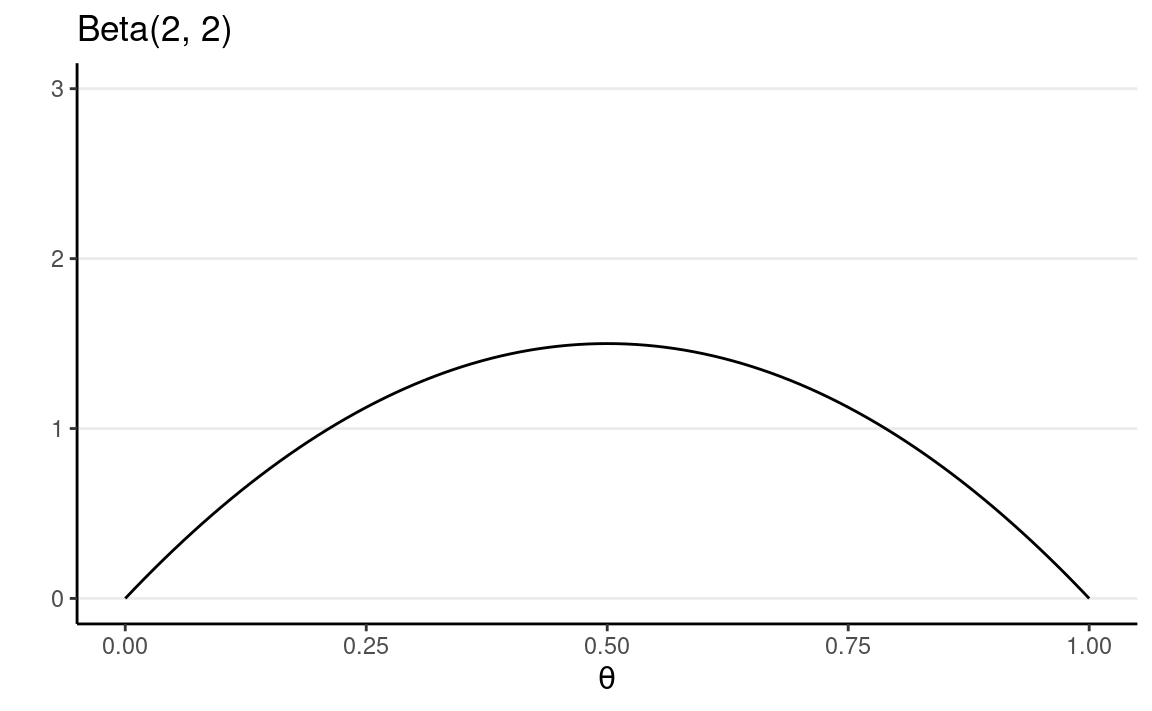

In this example, we will choose a weakly informative Beta(2, 2) prior, which represents a weak belief as below:

ggplot(tibble(th = c(0, 1)), aes(x = th)) +

stat_function(fun = dbeta, args = list(shape1 = 2, shape2 = 2)) +

ylim(0, 3) +

labs(y = "", x = expression(theta), title = "Beta(2, 2)")

Don’t Be Stubborn

One thing to remember is:

A good prior should give a non-zero probability/density for all possible values of a parameter

Otherwise, if the prior density for some parameter values is zero, the posterior density will be zero, regardless of how much the data support those parameter values

Data

count(Aids2, status)

#> status n

#> 1 A 1082

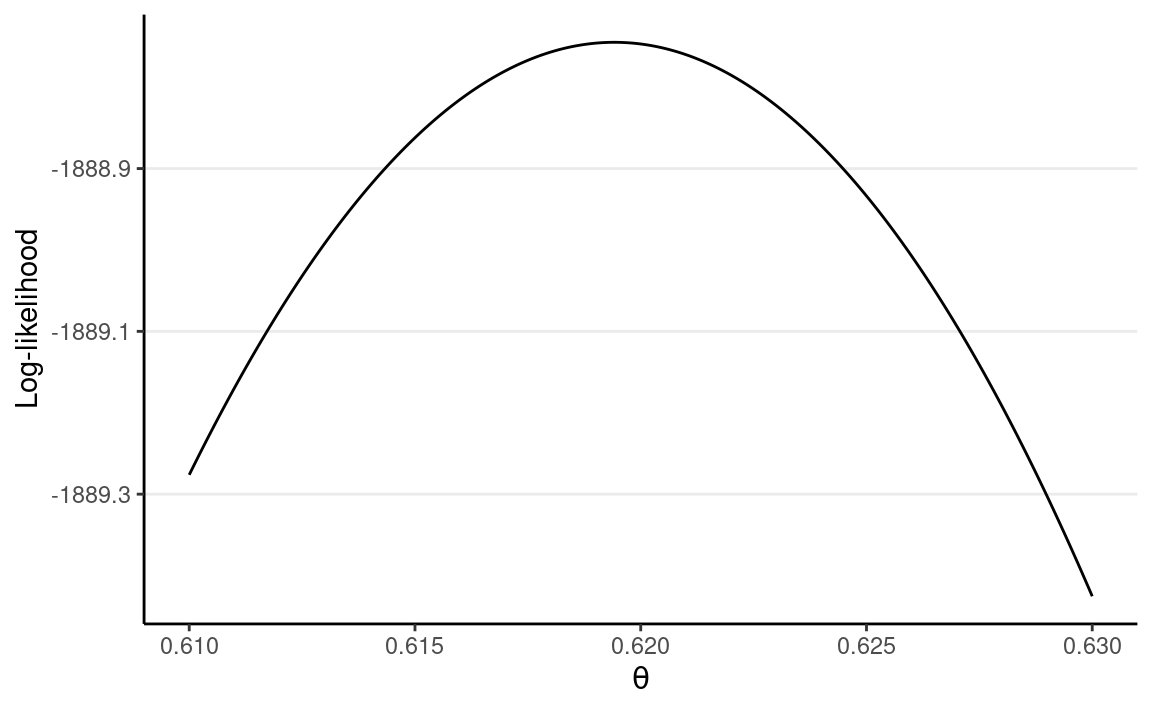

#> 2 D 1761The likelihood function is highly concentrated. I ran into some numerical issues as the computation gave zero, so I plotted the log-likelihood instead.

loglik <- function(th, N = 1082 + 1761, z = 1761) {

z * log(th) + (N - z) * log(1 - th)

}

ggplot(tibble(th = c(0.61, 0.63)), aes(x = th)) +

stat_function(fun = loglik, n = 501) +

labs(x = expression(theta), y = "Log-likelihood")

Note I only show a range of [0.610, 0.630] for the x-axis, which contains where the likelihood (thus also the log-likelihood) peaked.

Posterior

Based on the conjugacy, the posterior of θ is Beta(1,807, 1,116). As we’re

using a conjugate prior, the posterior is also a Beta distribution:

P(θ∣y)∼Beta(a+z,b+N−z),

Summarize the posterior

set.seed(2119)

num_draws <- 1000

sim_theta <- rbeta(num_draws, shape1 = 1807, shape2 = 1116)

c(`Bayes estimate` = mean(sim_theta),

`Posterior median` = median(sim_theta),

`Posterior SD` = sd(sim_theta),

`MAD` = mad(sim_theta),

`90% Credible interval (equal-tailed)` = quantile(sim_theta, probs = c(.1, .9)),

`90% HDI` = HDInterval::hdi(sim_theta, credMass = .9))

#> Bayes estimate

#> 0.618209694

#> Posterior median

#> 0.618382945

#> Posterior SD

#> 0.008829290

#> MAD

#> 0.009254166

#> 90% Credible interval (equal-tailed).10%

#> 0.606862338

#> 90% Credible interval (equal-tailed).90%

#> 0.628990588

#> 90% HDI.lower

#> 0.604051851

#> 90% HDI.upper

#> 0.632766654Posterior Predictive Check

Now, we need to know whether the model fits the data well. We don’t

have much to check for a Bernoulli model if we only have the

status variable. However, as there is information for other

variables, we can use them to check the exchangeability assumption. For

example, we can ask whether the data from different state categories are

exchangeable. The death rate across the 4 state categories are

#> status

#> state A D

#> NSW 664 1116

#> Other 107 142

#> QLD 78 148

#> VIC 233 355

#> status

#> state A D

#> NSW 0.3730337 0.6269663

#> Other 0.4297189 0.5702811

#> QLD 0.3451327 0.6548673

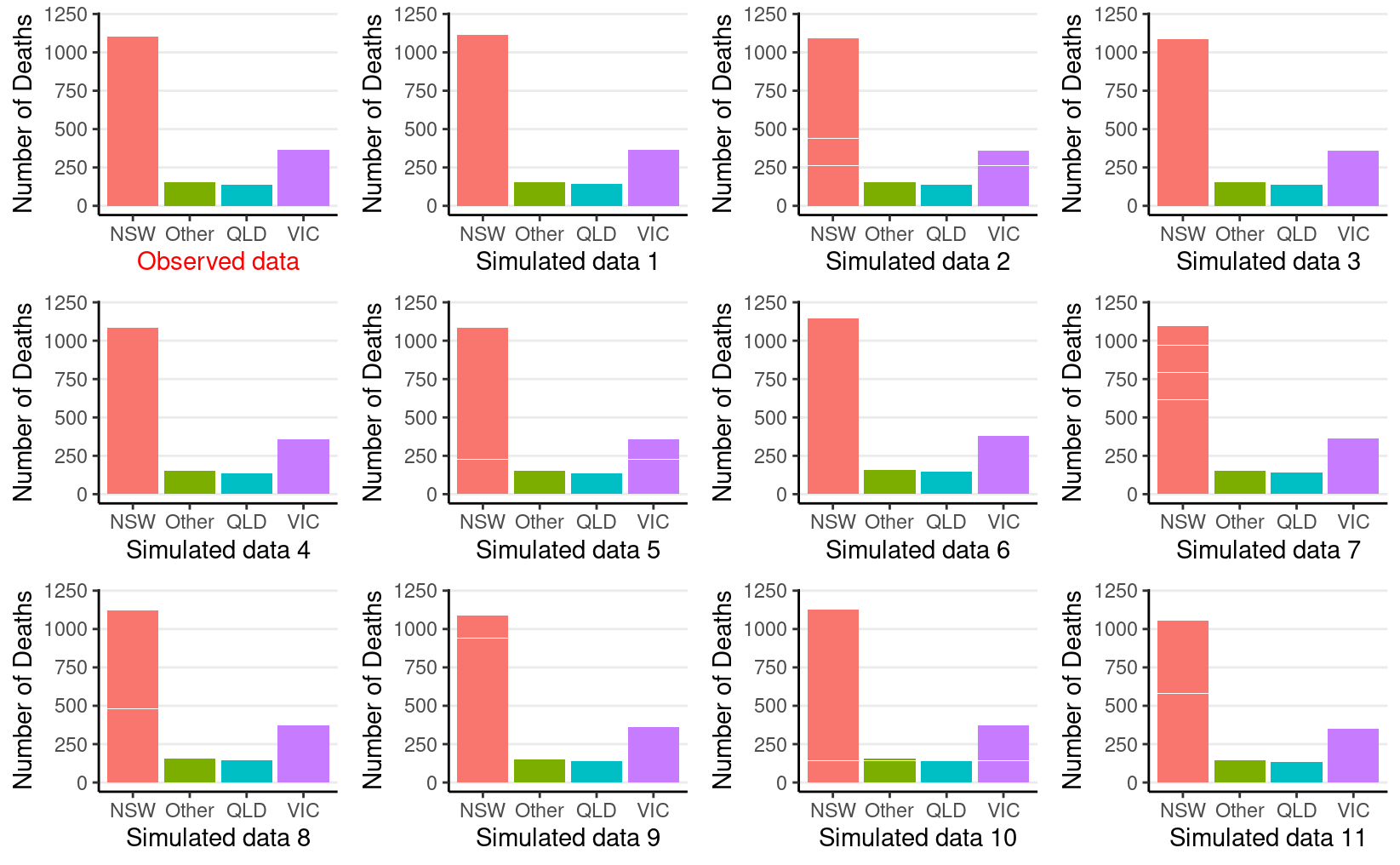

#> VIC 0.3962585 0.6037415Now, we can generate some predictions from our posterior distribution and our model.

plist <- vector("list", 12L)

plist[[1]] <- ggplot(

Aids2,

aes(x = state, y = mean(status == "D"), fill = state)

) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity") +

guides(fill = "none") +

labs(x = "Observed data", y = "Number of Deaths") +

theme(axis.title.x = element_text(color = "red")) +

ylim(0, 1200)

for (i in 1:11) {

# Get the a value from posterior samples

theta_post <- rbeta(1, 1763, 1084)

# For each plausible theta value, generate a status variable

status_new <- sample(c("D", "A"), nrow(Aids2),

replace = TRUE,

prob = c(theta_post, 1 - theta_post)

)

df_new <- Aids2 %>%

mutate(status = factor(status_new))

plist[[i + 1]] <- plist[[1]] %+% df_new +

labs(x = paste("Simulated data", i)) +

theme(axis.title.x = element_text(color = "black"))

}

gridExtra::grid.arrange(grobs = plist, nrow = 3)

So the observed data (the first subplot) look similar to the

simulated data. We can also conduct a posterior predictive check by a

test statistic for subgroups. Here we will use the

bayesplot package and look at fit across groups:

# Draw posterior samples of theta

post_sample <- rbeta(1e4, 1807, 1116)

# Initialize a S by N matrix to store the simulated data

y_tilde <- matrix(NA,

nrow = length(post_sample),

ncol = length(Aids2$status))

for (s in seq_along(post_sample)) {

theta_s <- post_sample[s]

status_new <- sample(c("D", "A"), nrow(Aids2),

replace = TRUE,

prob = c(theta_s, 1 - theta_s)

)

y_tilde[s,] <- as.numeric(status_new == "D")

}

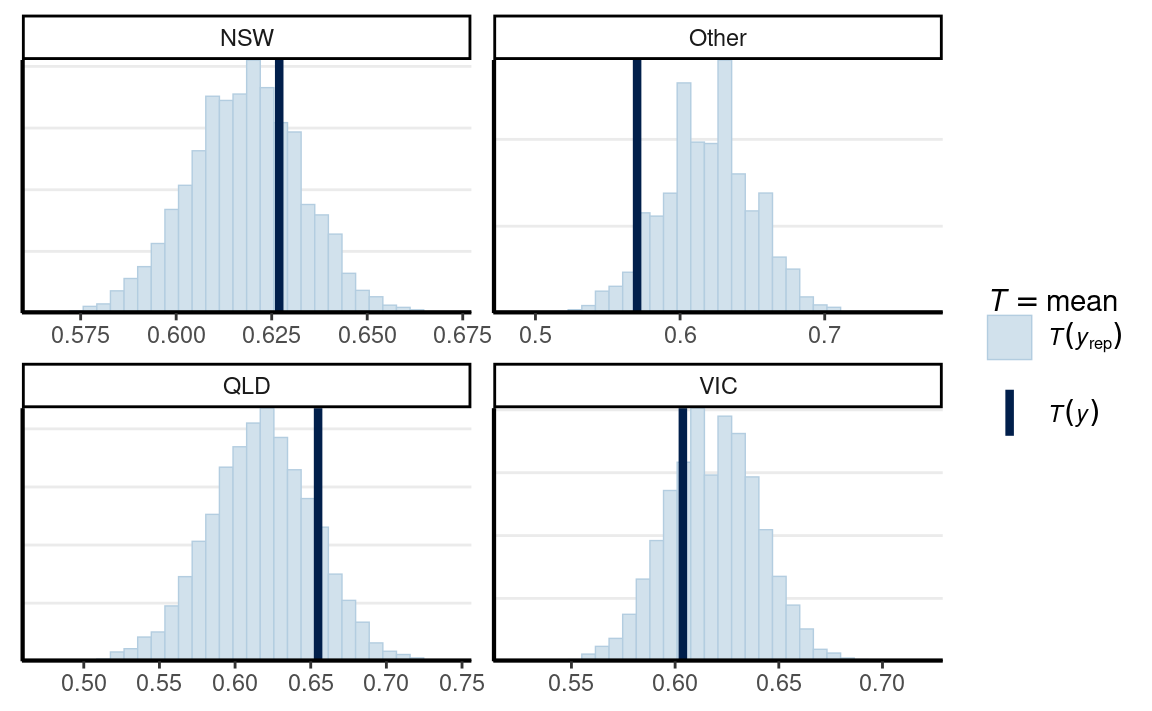

bayesplot::ppc_stat_grouped(

as.numeric(Aids2$status == "D"),

yrep = y_tilde,

group = Aids2$state

)

If the fit is good, the mean, indicated by the darker line, should be

within the simulated distribution based on the model. So the model that

assumes observations are exchangeable across states is not too off,

although it seems fitting less well for Other states.

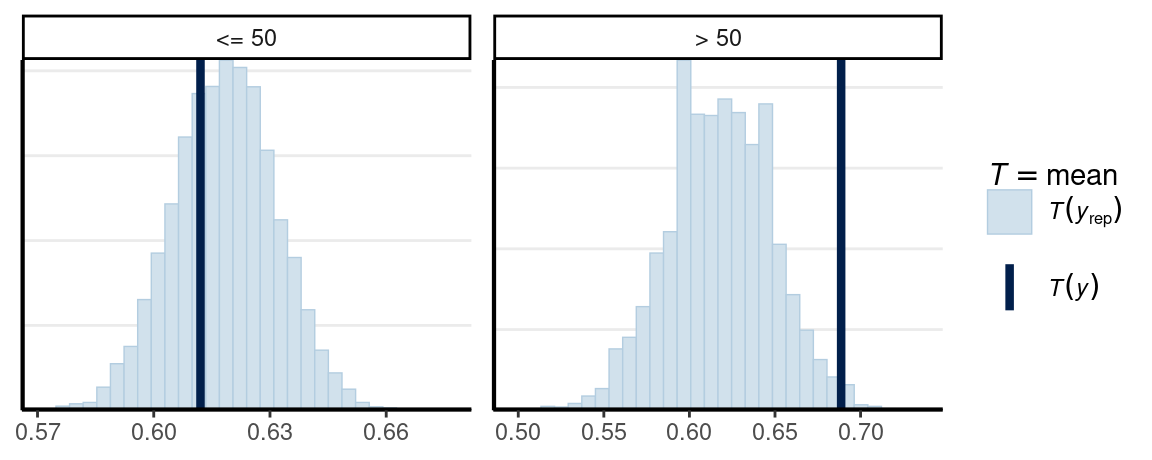

Another check on age

# Create an age group indicator

age50 <- factor(Aids2$age > 50, labels = c("<= 50", "> 50"))

# Draw posterior samples of theta

post_sample <- rbeta(1e4, 1807, 1116)

# Initialize a S by N matrix to store the simulated data

y_tilde <- matrix(NA,

nrow = length(post_sample),

ncol = length(Aids2$status))

for (s in seq_along(post_sample)) {

theta_s <- post_sample[s]

status_new <- sample(c("D", "A"), nrow(Aids2),

replace = TRUE,

prob = c(theta_s, 1 - theta_s)

)

y_tilde[s,] <- as.numeric(status_new == "D")

}

bayesplot::ppc_stat_grouped(

as.numeric(Aids2$status == "D"),

yrep = y_tilde,

group = age50

)

As can be seen, the model seems off for those aged 50+.

Comparison to frequentist results

Using maximum likelihood, the estimated death rate would be ˆθ=1761/2843=0.62, with a standard error (SE) of √0.62(1−0.62)/n=0.0091, with a 90% confidence interval of [0.6,0.63], which is similar to the interval with Bayesian inference.

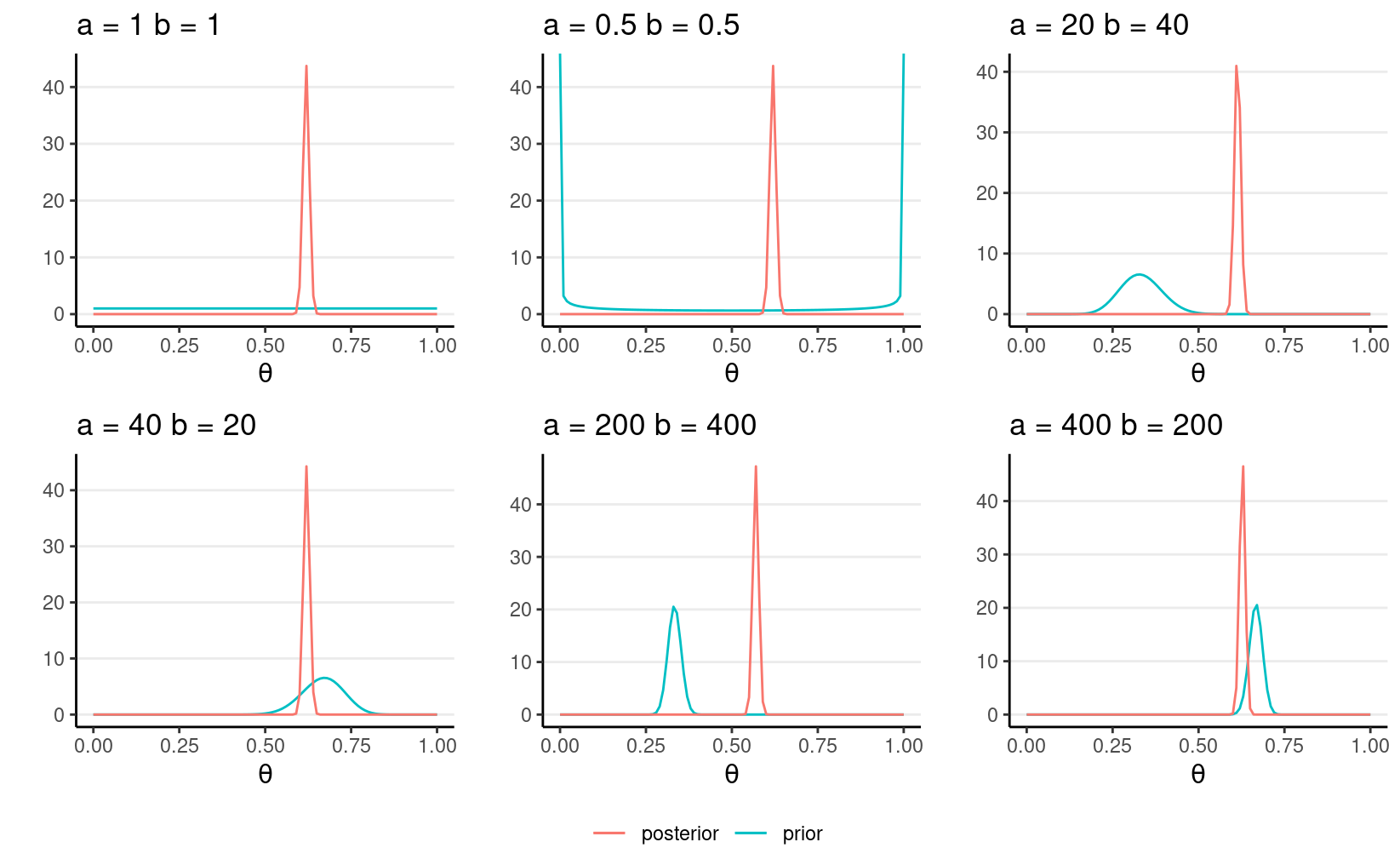

Sensitivity to different priors

You can see one needs a very strong prior (equivalent to 600 data points), and with the prior and the data not agreeing to get a substantially different conclusion.